So, what is a circuit breaker and why do we need them? If they keep tripping then surely they are the problem and we need to get rid of them? The misconception over fuses and circuit breakers, specifically those that fall into the Overcurrent Protective Devices (OCPDs) is widespread, including amongst electricians and technicians and the fundamentals of circuit protection is often not properly understood.

When too much electrical current flows through a cable, the current-carrying capacity of that cable is exceeded. If a small excess of current flows for a short period of time, it is unlikely that any long-term damage will occur, however if this is a frequent event, or a larger amount of current flows, the conductors of the cable will heat up. This can cause the insulation around the cable to be damaged, which can present an electric shock risk as well as a significant risk towards fires and electrical explosions.

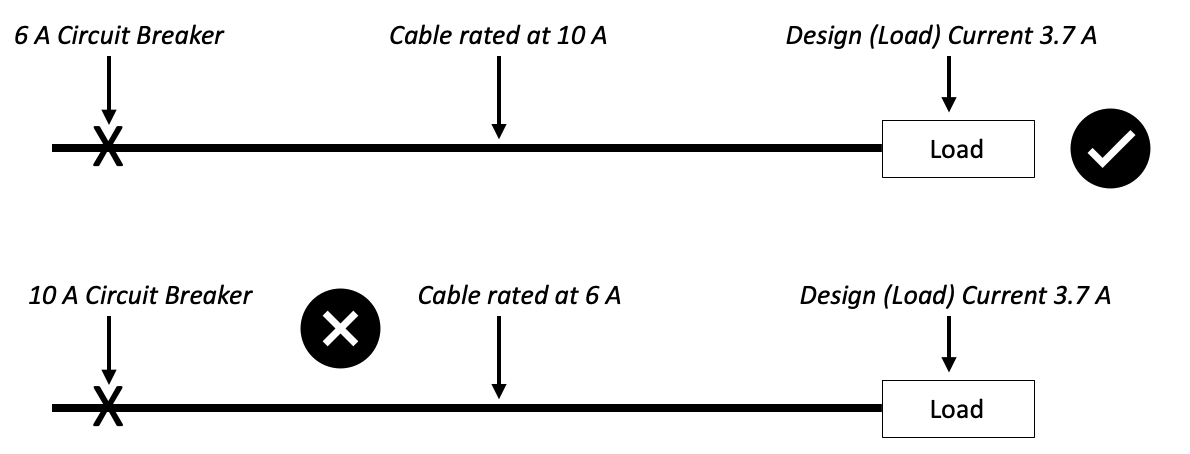

Electric current is measured in amps (A) we use the symbol I to indicate that we are talking about current, for example Ib = 3.7 A tells us the that design current (load current) of a circuit is 3.7 amps and In = 6 A tells us that the protective device is rated at 6 amps. A cable will have a current carrying capacity for its installed conditions which might be shown as Iz = 10 A (this means that the cable can carry 12 amps continuously with out getting so warm that insulation could be damaged).

In the electrical world the following should always be true: Ib ≤ In ≤ Iz which means that the design current of the circuit should not be higher than the rating of the fuse or circuit breaker which in turn should not be rated higher than the current-carrying capacity of the conductors of the cable.

An overcurrent Protective Device, often abbreviated to Protective Device is a fuse, circuit breaker or other devices that detects that too much current is flowing in a circuit and disconnects the supply before damage can occur. Circuit Breakers can be MCBs (Miniature Circuit Breakers, often referred to as Circuit Breakers), MCCBs (Moulded Case Circuit Breakers), ACBs (Air Circuit Breakers) OCBs (Oil Insulated Circuit Breakers) and VCBs (Vacuum Circuit Breakers) although other types of devices do exist.

There are two main categories of overcurrent (or fault current), these are overloads currents and short-circuit currents. Short- circuit currents typically include earth fault currents.

When an overload occurs, the circuit is carrying more current than it is designed to carry. There is nothing wrong with the wiring of the circuit (the circuit is said to be under fault-free conditions) however excessive load current is flowing. This may be because to many electrical appliances have been connected to the circuit, or the electrical load (such as a motor) is under excessive mechanical load, which in turn will draw more electric current as the motor tries to speed up and keep pace. Electrical circuits are designed to accommodate small overloads, infrequently that last for a short duration.

A short-circuit occurs when the circuit between live conductors (for example line and neutral) is bridged, or a line conductor comes into contact with earth. There is nothing in the circuit to impede the flow of current (in a.c. circuits we call this impedance, measured in ohms) or to resist the flow of current (in d.c. circuits we call this resistance, again measured in ohms), and as a result, very high values of current will flow. As a result, cables will get hot very quickly, the insulation on cables and conductors will melt and adjacent combustible materials will ignite.

The aim is to turn the power supply off before any damage occurs, before a fire starts or before a person is exposed to a live electrical part.

Although there are instances where fuses are used instead of circuit breakers, circuit breakers are commonly seen in domestic and commercial applications. There are many benefits to using a circuit breaker over a fuse, including the ease of restoring the supply when a device trips.

Within UK domestic properties it is likely that the following circuits will be installed with the following size circuit breakers:

- Lighting circuits 6 amp circuit breaker

- Immersion heater 16 amp circuit breaker

- Supplies to sheds 20 amp circuit breaker

- Socket circuits 32 amp circuit breaker

- Cooker circuits 32 amp circuit breaker

- Shower circuits 40 amp circuit breaker

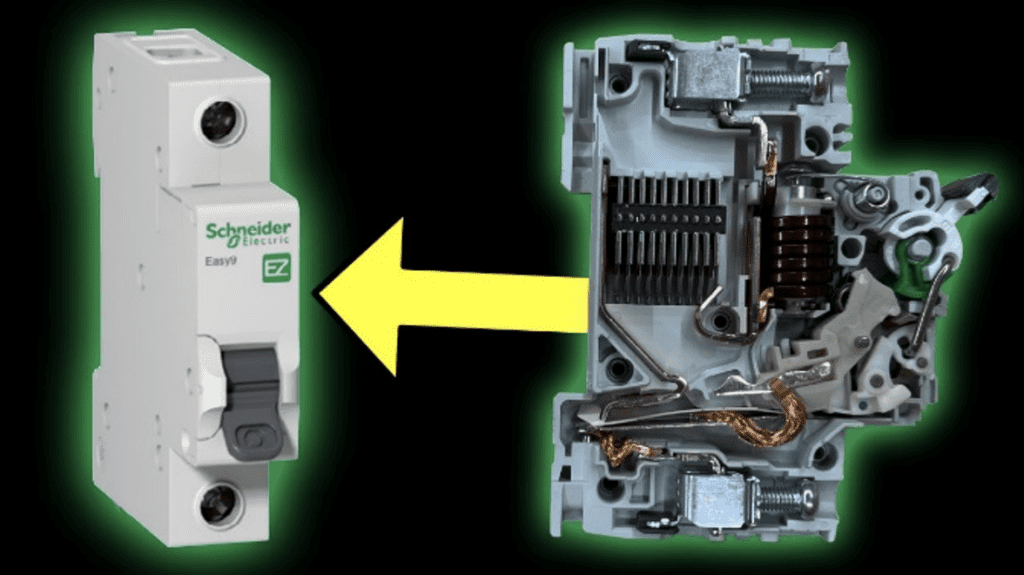

What is inside a circuit breaker? A typical Miniature Circuit Breaker to BS EN 60898 found in most domestic and commercial applications is correctly referred to as a thermal and magnetic device which accurately describes the two methods used to detect overcurrent: a bi-metallic strip that detects overloads and an electromagnetic coil that detects short-circuits.

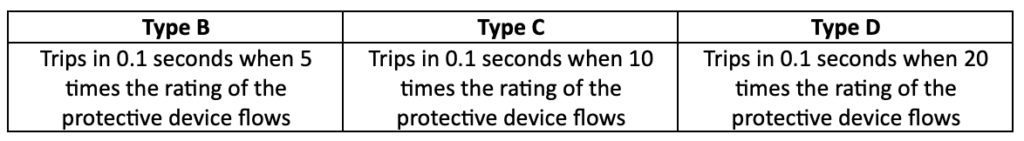

The rating of the circuit breaker is the maximum steady-state current that the device is able to continuously carry. Circuit breakers will not operate when lower values of current are flowing, but will trip when excess current flows, however, the amount of current flowing will dictate how long it takes for the circuit breaker to operate. Under overload conditions that may be many minutes, in the case of short-circuits, this will typically be around 0.1 seconds. You may notice that circuit breaker ratings may be preceded by a letter, such as B6, D10 or C16. The letter indicates the sensitivity of the circuit breaker:

We use different types of circuit breakers dependant on the types of loads connected to a circuit.

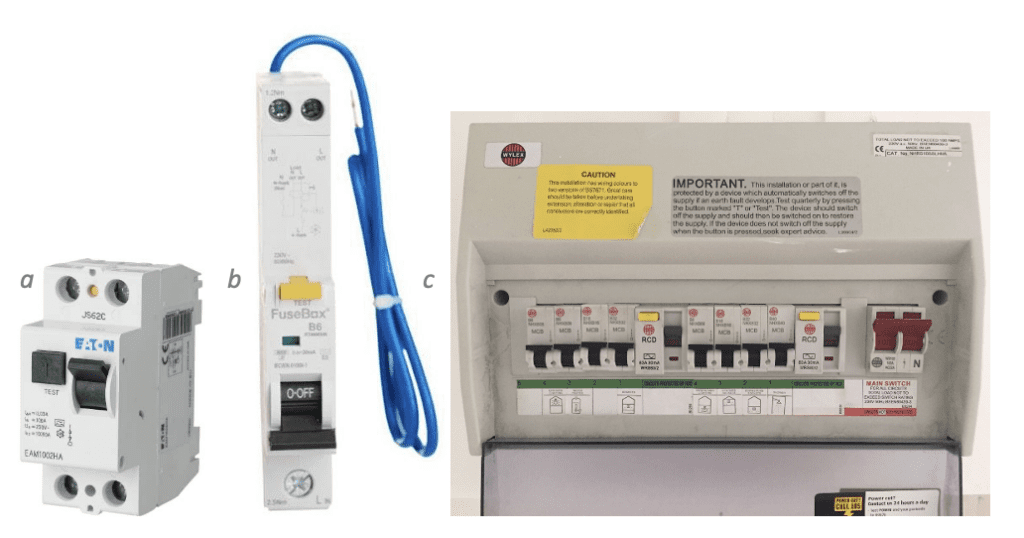

We also include Residual Current Devices or RCDs to keep people safe. RCDs can be sub-divided into Residual Current Circuit Breakers (RCCBs) and Residual Current Breakers with Overcurrent (RCBOs), as well as RCD plugs, sockets and spurs. An RCCB is an RCD with no other protective device features incorporated, whereas an RCBO is an MCB and an RCD combined into the same unit.

A: RCCB

B: RCBO

C: Typical UK Consumer Unit containing RCCBs and MCBs.

It is common within the UK and Europe to find an RCCB protecting a number of MCBs. Although there is an initial installation cost to using RCBOs in place of separate RCCBs and MCBs, the level of convenience offered through limited disruption when a fault occurs makes their use attractive to electrical consumers.

There are three rules to remember when resetting circuit breakers:

Rule 1- circuit breakers do not trip for no reason. Circuit breakers only operate when too much current has passed through the device.

Rule 2- turning a circuit breaker back on to a fault will not improve the situation. Constantly resetting a device can only lead to more damage and runs the risk of the protective device being damaged.

Rule 3- circuit breakers protect us from electric shock (fault-protection), fires and explosions. If we override, adjust or abuse them we will not be protected.

Resetting a circuit breaker

- Do not take any risks, if in doubt, call in a competent person.

- Establish what has gone off. Determine the extent of the disruption. If lights and power have gone off it may be that an RCCB has tripped, a distribution fuse has blown, or there may be a power cut. Look at what is still working and whether your neighbours still have power. Note. During a power cut it might be that adjoining neighbours still have power, however some properties and streetlights may be in darkness. This is a partial power cut that will affect around a third of properties in your locality. In the case of a power cut dial 105 to report the issue.

- Go to your consumer unit and identify which devices, if any have operated. It may be that an RCCB or an MCB has tripped, but could also be that both an RCCB and an MCB has tripped simultaneously.

- Check the circuit chart or device label to verify that the device label matches with the devices that have stopped working.

- Check for signs of damage, both at the consumer unit and around the affected circuit / equipment. Looks for signs of cable damage / crushing as well as signs of heat damage. Verify there is no water ingress and no broken electrical casings.

- Turn off electrical switches and where appropriate unplug electrical appliances.

- If there is no cause for concern, turn the circuit breaker back on. Do this once only within a 24-hour period. If the circuit breaker turns off straight away, then do not reset a second time. Consult a competent person.

- If the circuit breaker stays on, go around each switch and plug and turn them on one by one. If the circuit breaker trips again when a load or appliance is switched back on or plugged back in, it is likely that it is that appliance that is defective and must be switched back off or unplugged.

- If everything comes back on, monitor the circuit for signs of damage or deterioration.

- If an RCCB has tripped, turn off all of the circuit breakers and try to turn the RCCB back on. If the RCCB stays on, turn each MCB back on, one at a time. If the RCCB trips when you turn a specific MCB back on, this is the circuit that is faulty. Turn that MCB back off and reset the RCCB. Continue to reset all of the other MCBs and the RCCB should stay on. Return to step 6 and disconnect all appliances on the affected circuit and try to restore the circuit breaker as outlined in step 8.

- If a circuit breaker trips again and the cause is not known, a competent person will be required to attend so that more detailed testing can be carried out to identify the cause of the fault.